Gå offline med appen Player FM !

Labor Day: The Ruth Shaver Story

Manage episode 437698783 series 56780

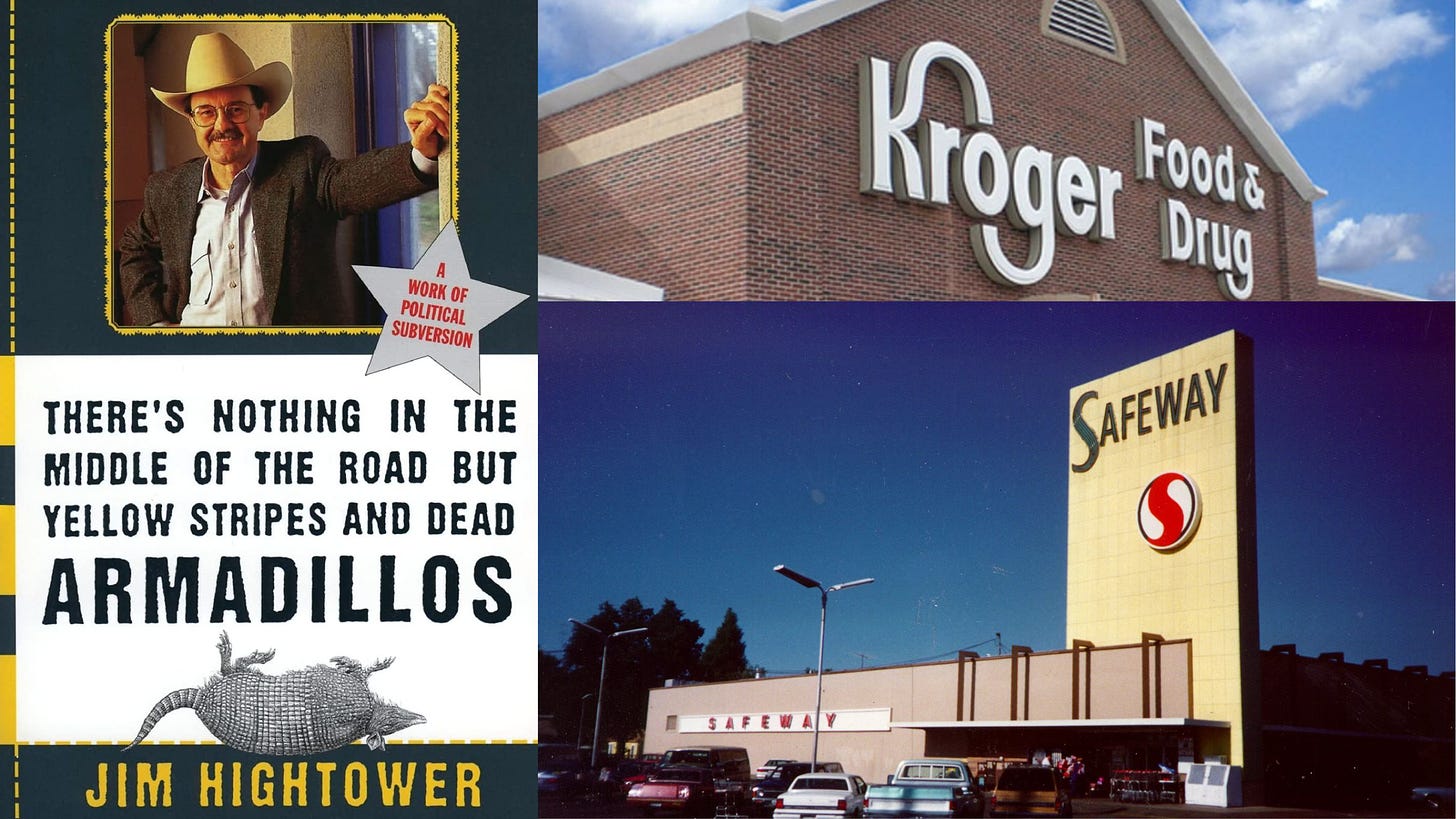

Just before Labor Day, FTC Chairwoman Lina Khan kicked off a momentous antitrust lawsuit, challenging the $24 billion monopolistic plan by grocery giant Kroger to take over the Albertson supermarket chain. The mega-merger would drastically shrivel competition, raise our grocery prices, eliminate thousands of jobs, and reduce bargaining power for unionized workers.

Top executives of the two chains would make a killing, as would the Wall Street bankers and elite law firms engineering the merger. It’s a textbook case of how inequality is intentionally created.

Media coverage of such cases focuses almost entirely on legal tactics and on which side is winning the ballgame. But for the 700,000 employees caught up in this merger, it’s not a game. Instead of economic statistics and arcane corporate law, the merger is about lives, family, equality, cold betrayal, and personal loss.

Years ago, I wrote about the human cost and social rupture that are inherent (though mostly ignored) in these high-flying money deals. In my 1997 book, There’s Nothing in the Middle of the Road But Yellow Stripes and Dead Armadillos, I told the story of Ruth Shaver. A proud and valuable frontline worker in a Safeway supermarket for 22 years, her future was suddenly slammed from out of nowhere by a group of profiteering Wall Street raiders. They used a junk-bond scam to take over the Safeway chain… and Ruth’s life.

Here's her story, which, all these years later, is directly relevant to Kroger’s current takeover scheme—and a vivid reminder that Labor Day is not a holiday, but a call to action.

Let me introduce you to Ruth Shaver of Mesquite, Texas.

She worked for Safeway for twenty-two years until one day in July 1986, when something called "Kohlberg Kravis Roberts" dropped out of the sky and took over her company... and her job.

KKR is a firm of Wall Street pirates that specializes in raiding corporations. Armed with more than $4 billion in junk bonds, they leaped on Safeway and claimed it as their own—three gentlemen who would not know how to bag a line of groceries if their lives depended on it suddenly owned the country's biggest supermarket chain.

Four billion dollars is a hell of a debt load to carry, even for pirates, so to lighten it, KKR immediately began ripping up big pieces of Safeway's assets and throwing them overboard. Believe it or not, this is what passed for good business sense in the eighties. Among the assets they chunked was the entire Dallas division of the company—141 Safeway stores, along with 8,814 Safeway people. Bam! Out the door.

Ruth Shaver was one of them.

No one was a more cheerful, dedicated, loyal, and capable employee than Ruth was for Safeway. She checked groceries, bagged them, stocked shelves, trained others, and helped remodel stores. She took great pride in her work and had the kind of attitude that caused customers to ask for her by name, and if she was checking, they'd wait in her line even if if was longer than the others. For a lot of people, Ruth Shaver was Safeway.

Over the years, she worked her way up to wages of $12.06 an hour, about $24,000 a year—not enough to summer in France, but enough to buy a small slice of middle-class America.

With no notice, though, or fare-thee-well, her store was abruptly closed and she was dumped. "They left me high and dry," Ruth says. Because of her union's contract, she did get a small severance payment, but it lasted only a few weeks, after which she was stretched to the breaking point. Of course, she had begun looking for work immediately, but she was one of 8,800 people put on the market at once, and the Dallas job market in the late eighties was already a disaster.

It took her seven months to land another job—not one at twelve bucks an hour, but $5.70, plummeting her from that middle-class income of $24,000 to under $12,000 a year. At these wages, she couldn't keep up the payments on her Buick, so she lost it, along with her good credit rating.

But Ruth is a scrapper. She got an old clunker of a car and began struggling back. After a couple of years, she was working two jobs—she would leave her trailer house at 10:30 P.M. for the night shift at a warehouse, get of at 7 A.M., then drive across town for an 8-to-noon part-time position at a local grocery store. Ten years later, she is finally working full time again at a grocery store, and is up to $10.85 an hour. Also, she now drives a '90 Hyundai, though she had to buy it in her son's name since her credit was shot, but even that is beginning to recover—she recently got a Penney's charge card.

Like Ruth, the 8,813 other Safeway employees were a long time finding other jobs (a third were unable to find employment for more than two years), and when they did get jobs, practically everyone had to swallow pay cuts of 30 to 60 percent. Four committed suicide. The divorce rate among these families has been epidemic, and the former employees have suffered an abnormally high number of heart attacks.

On the other end of the Safeway takeover, though, the picture has been a whole lot brighter. Jerome Kohlberg, Henry Kravis, and George Roberts each enjoyed personal incomes of more than $40 million the year they bounced Ruth and her coworkers. Henry Kravis has become one of the 400 richest people in America and often gets his picture in the society pages partying with Oscar de al Renta and the high-hat fun crowd in New York City. He was cochair of New York's "Bush for President" finance committee in '88. But don't pigeonhole him as an unbending Republican—in that same year, he was a major contributor to Senators Bill Bradley, Lloyd Bentsen, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, and other Democratic lawmakers up for reelection. (Call me a galloping Trotskyite if you must, but am I the only one who suspects this financial cross-pollination by the Kravises of our country is the reason neither party ever does anything about their piratical ways?)

Then Mr. Kravis took the plunge that so many superfluously wealthy corporate marauders take: He became a "philanthropist." Not a modest one, of course—Henry wanted full credit and a major public fuss made over him, and you can be assured he grabbed a full tax deduction for his generosity. He donated $10 million to New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art. In return, the museum named a wing of its building after him

So Henry Kravis got the glory as well as the gold. But you know, there are bricks in that wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art that belong to 8,814 Safeway employees, including Ruth Shaver, who still lives in a trailer in Mesquite, Texas.

Update, 2024: Ruth passed away in 2004 at 61 years old.

Jim Hightower's Lowdown is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

632 episoder

Manage episode 437698783 series 56780

Just before Labor Day, FTC Chairwoman Lina Khan kicked off a momentous antitrust lawsuit, challenging the $24 billion monopolistic plan by grocery giant Kroger to take over the Albertson supermarket chain. The mega-merger would drastically shrivel competition, raise our grocery prices, eliminate thousands of jobs, and reduce bargaining power for unionized workers.

Top executives of the two chains would make a killing, as would the Wall Street bankers and elite law firms engineering the merger. It’s a textbook case of how inequality is intentionally created.

Media coverage of such cases focuses almost entirely on legal tactics and on which side is winning the ballgame. But for the 700,000 employees caught up in this merger, it’s not a game. Instead of economic statistics and arcane corporate law, the merger is about lives, family, equality, cold betrayal, and personal loss.

Years ago, I wrote about the human cost and social rupture that are inherent (though mostly ignored) in these high-flying money deals. In my 1997 book, There’s Nothing in the Middle of the Road But Yellow Stripes and Dead Armadillos, I told the story of Ruth Shaver. A proud and valuable frontline worker in a Safeway supermarket for 22 years, her future was suddenly slammed from out of nowhere by a group of profiteering Wall Street raiders. They used a junk-bond scam to take over the Safeway chain… and Ruth’s life.

Here's her story, which, all these years later, is directly relevant to Kroger’s current takeover scheme—and a vivid reminder that Labor Day is not a holiday, but a call to action.

Let me introduce you to Ruth Shaver of Mesquite, Texas.

She worked for Safeway for twenty-two years until one day in July 1986, when something called "Kohlberg Kravis Roberts" dropped out of the sky and took over her company... and her job.

KKR is a firm of Wall Street pirates that specializes in raiding corporations. Armed with more than $4 billion in junk bonds, they leaped on Safeway and claimed it as their own—three gentlemen who would not know how to bag a line of groceries if their lives depended on it suddenly owned the country's biggest supermarket chain.

Four billion dollars is a hell of a debt load to carry, even for pirates, so to lighten it, KKR immediately began ripping up big pieces of Safeway's assets and throwing them overboard. Believe it or not, this is what passed for good business sense in the eighties. Among the assets they chunked was the entire Dallas division of the company—141 Safeway stores, along with 8,814 Safeway people. Bam! Out the door.

Ruth Shaver was one of them.

No one was a more cheerful, dedicated, loyal, and capable employee than Ruth was for Safeway. She checked groceries, bagged them, stocked shelves, trained others, and helped remodel stores. She took great pride in her work and had the kind of attitude that caused customers to ask for her by name, and if she was checking, they'd wait in her line even if if was longer than the others. For a lot of people, Ruth Shaver was Safeway.

Over the years, she worked her way up to wages of $12.06 an hour, about $24,000 a year—not enough to summer in France, but enough to buy a small slice of middle-class America.

With no notice, though, or fare-thee-well, her store was abruptly closed and she was dumped. "They left me high and dry," Ruth says. Because of her union's contract, she did get a small severance payment, but it lasted only a few weeks, after which she was stretched to the breaking point. Of course, she had begun looking for work immediately, but she was one of 8,800 people put on the market at once, and the Dallas job market in the late eighties was already a disaster.

It took her seven months to land another job—not one at twelve bucks an hour, but $5.70, plummeting her from that middle-class income of $24,000 to under $12,000 a year. At these wages, she couldn't keep up the payments on her Buick, so she lost it, along with her good credit rating.

But Ruth is a scrapper. She got an old clunker of a car and began struggling back. After a couple of years, she was working two jobs—she would leave her trailer house at 10:30 P.M. for the night shift at a warehouse, get of at 7 A.M., then drive across town for an 8-to-noon part-time position at a local grocery store. Ten years later, she is finally working full time again at a grocery store, and is up to $10.85 an hour. Also, she now drives a '90 Hyundai, though she had to buy it in her son's name since her credit was shot, but even that is beginning to recover—she recently got a Penney's charge card.

Like Ruth, the 8,813 other Safeway employees were a long time finding other jobs (a third were unable to find employment for more than two years), and when they did get jobs, practically everyone had to swallow pay cuts of 30 to 60 percent. Four committed suicide. The divorce rate among these families has been epidemic, and the former employees have suffered an abnormally high number of heart attacks.

On the other end of the Safeway takeover, though, the picture has been a whole lot brighter. Jerome Kohlberg, Henry Kravis, and George Roberts each enjoyed personal incomes of more than $40 million the year they bounced Ruth and her coworkers. Henry Kravis has become one of the 400 richest people in America and often gets his picture in the society pages partying with Oscar de al Renta and the high-hat fun crowd in New York City. He was cochair of New York's "Bush for President" finance committee in '88. But don't pigeonhole him as an unbending Republican—in that same year, he was a major contributor to Senators Bill Bradley, Lloyd Bentsen, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, and other Democratic lawmakers up for reelection. (Call me a galloping Trotskyite if you must, but am I the only one who suspects this financial cross-pollination by the Kravises of our country is the reason neither party ever does anything about their piratical ways?)

Then Mr. Kravis took the plunge that so many superfluously wealthy corporate marauders take: He became a "philanthropist." Not a modest one, of course—Henry wanted full credit and a major public fuss made over him, and you can be assured he grabbed a full tax deduction for his generosity. He donated $10 million to New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art. In return, the museum named a wing of its building after him

So Henry Kravis got the glory as well as the gold. But you know, there are bricks in that wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art that belong to 8,814 Safeway employees, including Ruth Shaver, who still lives in a trailer in Mesquite, Texas.

Update, 2024: Ruth passed away in 2004 at 61 years old.

Jim Hightower's Lowdown is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

632 episoder

Tất cả các tập

×Velkommen til Player FM!

Player FM is scanning the web for high-quality podcasts for you to enjoy right now. It's the best podcast app and works on Android, iPhone, and the web. Signup to sync subscriptions across devices.